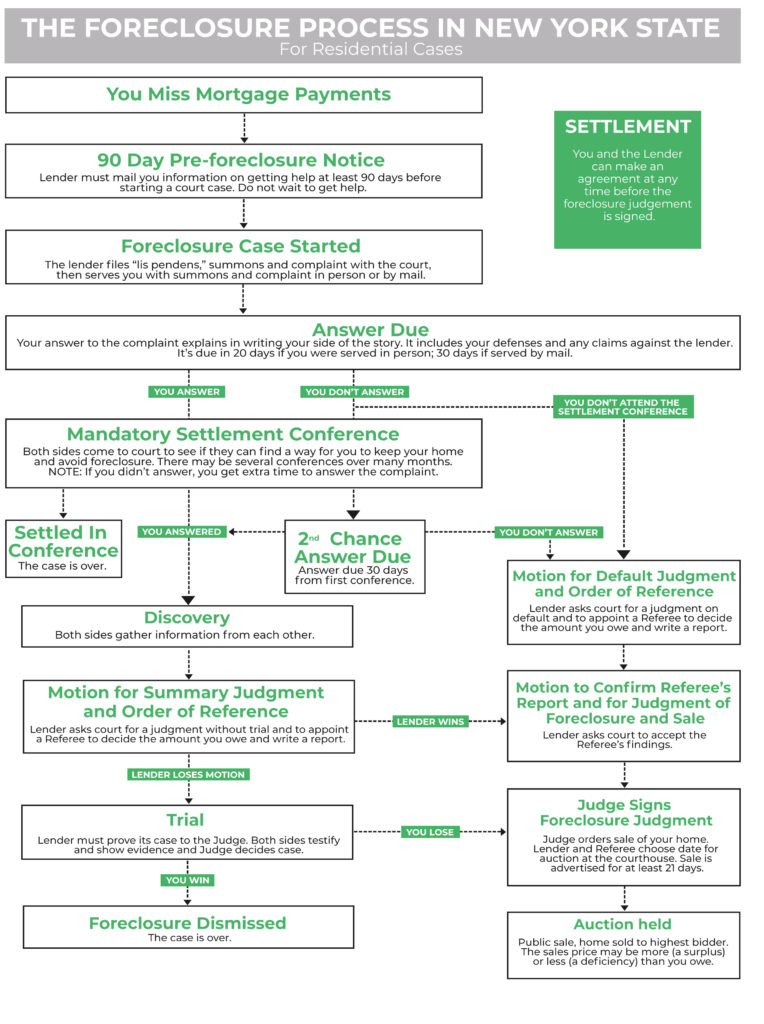

One lawyer who specializes in foreclosures in New York told us that theoretically borrowers could go back to mandatory settlement conference 10 or 11 times if they aren’t able to make an agreement with the lender.

Keep in mind that during all of this time, everything is stopped until a determination can be made on whether a loan modification might be agreeable.

This can go on for a couple of years, and often times the bank will simply give up and agree to a favorable loan modification.

Remember that the courts in New York tend to be so liberal that they’d allow borrowers with no income to keep coming back to court to delay the process. Why? Because the extremely liberal courts in New York simply don’t want foreclosures to happen.

The discovery process if no settlement is made

If a settlement is made during the conference, then the case is over. If however a settlement can’t be agreed on, both parties will then gather information from each other during what’s called the discovery process.

During discovery, the borrower’s attorney will serve the bank’s attorney with discovery demands such as proof of the chain of title, payment history, etc.

Note that the courts in New York tend to put the onus on banks’ attorneys to certify that everything in the summons and complain is true, and that all original documents referenced are in their possession.

This can be a real problem for lenders if the loan was actually originated by another bank, and has hence been sold or assigned one or more times.

Savvy borrower’s attorneys could claim that the lender has no standing and doesn’t have the right to bring action if the bank wasn’t the original lender and doesn’t have the original paperwork.

For example, the bank could be in real trouble if it fails to provide proof of the chain of title, all the way from the original promissory note to every assignment to a new lender.

Motion for summary judgment and order of reference

After the discovery process where the lender will also collect information from the borrower such as pay stubs and account statements, the lender will ask the court for a judgment without trial and for the court to appoint a referee (i.e. usually an attorney) to decide the amount owed.

Keep in mind that a summary judgment means there’s no issue of fact yet to be determined, and that this is rarely the case in real life.

Regardless, banks will make this motion and then it will take another 5 to 6 months to get in front of a judge. Note that it can take up to a year or we’ve even heard 2 years to get a decision on the motion.

Motion for default judgment and order of reference

If the borrower doesn’t answer the 90 day pre-foreclosure notice and doesn’t attend the mandatory settlement conference, then the lender can ask the court for a judgment on default, and to appoint a referee (i.e. again usually an attorney) to decide on the amount the borrower owes.

Motion to confirm referee’s report and for judgment of foreclosure and sale

If the lender wins the motion for summary judgment or the motion for default judgment, then the lender asks the court to confirm the referee’s findings.

Note that it’s possible at this stage just like any other stage for the borrower to delay proceedings. At this stage, the borrower could simply challenge the referee’s report to further prolong the process.

Judge signs judgment of foreclosure and sale

The judge signs the foreclosure judgment and orders the sale of the borrower’s home. The lender and the referee then choose an auction date at the local courthouse (i.e. typically the county courthouse’s steps).

The sale must be advertised once a week for 3 weeks in a local newspaper. The advertisement will list the property’s address and list when and where the foreclosure auction has been scheduled as well as the estimated amount owed to the lender.

The foreclosure auction is finally held

On the day of the public sale, the “upset price” will be posted outside the courtroom which is kind of a reserve price for the bank. The upset price is typically the amount owed by the borrower, plus any fees, interest and any other costs accumulated in the interim.

If the property sells for more than the upset price, then that additional money is called a “surplus” to which the borrower is entitled. The former homeowner will need to make a motion in court to get that surplus, which is essentially the borrower’s home equity less any fees, interest and expenses incurred by the bank.

In rising markets, we’ve seen cases where a borrower who hasn’t paid their mortgage in years ends up actually making money in a foreclosure because home prices have risen significantly.

If on the other hand the property is sold to the highest bidder and the amount is less than the upset price, then we have what you call a “deficiency.” In a deficiency scenario, the bank is still owed some money and can sue for the difference. However, the bank will only have 90 days to initiate proceedings after the foreclosure sale.

It’s interesting to note that once a foreclosure takes place, all junior liens including home equity loans and mechanic’s liens are wiped out and no longer secured by anything.

So this means all junior debts effectively become unsecured debts like credit card debt, and thus 2nd lien lenders will need to also sue to recover their deficiency immediately after the foreclosure happens.

A trial happens if the lender loses the motion for summary judgment

The last possibility to explore is the scenario where a mandatory settlement conference fails to produce an agreement, and the judge declines the lender’s motion for summary judgment after the discovery phase.

In this situation, a trial occurs and the lender must prove its case to the judge. Both sides will testify and show evidence, and the judge makes a decision.

As previously discussed, the onus is often more on the lender than the borrower in New York’s liberal minded courts. The bank will have to prove that they have everything in order such as the chain of title, payment history etc.

This process can easily take several months, but remember, the courts are inclined to make life difficult for lenders and to do everything possible to force big banks to settle with homeowners.

It’s interesting to note that the mandatory settlement conference was only initially meant for primary residences. But courts in NY ended up offering it for second homes, HELOCs, co-ops, reverse mortgages, investment properties etc.

The mandatory settlement conference has never been repealed, so it’ll be interesting to see it in play for the current Coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

It’s interesting that condo boards can file a lawsuit for unpaid common charges (i.e. common charge lien) and ultimately get a judgment, which impedes the owner from being able to sell the condo. The board would also have the right to foreclose on the common charge lien.

However, very interestingly, whoever buys the foreclosed condo in that scenario would be subject to the original mortgage on the property, which is superior to the more junior common charge lien.

Now for co-ops, it’s almost like the reverse of the process in this article since foreclosures for co-ops are subject to the UCC (i.e. it’s non judicial) since it’s not real property.

The co-op board will give a delinquent shareholder tenant 30 days notice, then the board will need to publish the sale in a local newspaper, the shareholder gets a certified letter that the board intends to sell their unit and the sale is conducted at the local court house. Generally, it’ll be the bank lender that’s the foreclosing party.

Now co-op shareholders in New York can file a special proceeding and can usually get the courts to agree to a settlement process, but they have to move quickly because a co-op foreclosure moves very quickly.

The extremes described in this article won’t be for everyone. Not everyone wants to take maximum advantage of the liberal court system here in New York but destroy their credit score.

This is why many borrowers in trouble try to get the lender to agree to a short sale, which is reported on one’s credit report as “settled for less.” While that’s not great either, it’s still way better than being foreclosed upon which is the worst for one’s credit.

One thing to keep in mind, a short sale can be considered forgiveness of debt by the government, and form 1099-C reports that “income” from the forgiveness of debt (i.e. the amount the bank was “short” by agreeing to a short sale).

With that said, for years short sellers didn’t have to report this as income if it was their primary residence, though I’m not actually certain now with the new tax laws. Anyone know?

Quick addition to this great article, if the borrower is released from the mandatory settlement process, the court usually gives a 60 day stay on action. Thus, more free time in the home for the borrower.

Another delaying tactic is for the borrower to agree to a trial modification, and if the borrower makes these trial payments then the bank has to discontinue the foreclosure case. Then, if the borrower falls behind again, the poor bank has to restart the whole process again!

Regarding short sales, yes they’re interesting opportunities for investors, but just like foreclosures you have to be careful. For short sales, the property can easily come with open water and sewer bills for example.

Also, it’s important to get a release from the 1st and 2nd lender (if any) in a short sale purchase. Lastly, perhaps you can consider a cash for keys program, like $2k to $10k as a financial incentive for the seller to show up to closing with the keys.

Last interesting side note, banks usually have a separate short sale department with its own underwriting team.

Filing bankruptcy right before a foreclosure auction is supposed to happen is a common stall tactic in New York, but it is by no means foolproof.

We had a recent example where we anticipated that a delinquent borrower was going to file for bankruptcy again, after failing to go through with the repayment plan as we expected after filing for bankruptcy the first time.

We petitioned the court to allow us to continue with the foreclosure if they tried to file for bankruptcy again to stall the sale. Lo and behold, they filed for bankruptcy a second time right before our second attempt to conduct the foreclosure sale, but the court order protected us, we re-noticed the foreclosure and were able to sell the condo unit. This was a condo common charge lien foreclosure by the way.